It was an ordinary soccer pitch: sparse tufts of grass and reddish soil surrounded by cinder-block homes. The two candidates stood on opposite sides of the field as the people of Yelwa, a town of 30,000 in central Nigeria, lined up behind them one May morning in 2002 to vote. Whoever had more supporters would lead the town’s council. And whoever led the council would control the certificates of indigeneship: the papers certifying that Yelwa was their home, and that they had a right there to land, jobs, and scholarships. Between the iron goalposts milled ethnic Jarawa, principally Muslim merchants and herders; next to them were the Tarok and Goemai, predominantly farmers and Christians. For several years, their hereditary tribal chief, a Christian, had refused certificates of indigeneship to Muslims no matter how long they’d lived in Yelwa. Without the certificates, the Muslims were second-class citizens.

As the two groups waited in the heat to be counted, the meeting’s tone soured. “You could feel the tension in the air,” Abdullahi Abdullahi, a 55-year-old Muslim lawyer and community leader, said later. A tall, thin man with a space between his two front teeth and shoulders hunched around his ears in perpetual apology, he was helping to direct the crowd that day. No one knows what happened first. Someone shouted arna—infidel”—at the Christians. Someone spat the word jihadi at the Muslims. Someone picked up a stone. “That was the day ethnicity disappeared entirely, and the conflict became just about religion,” Abdullahi said. Chaos broke out, as young people on each side began to throw rocks. The candidates ran for their lives, and mobs set fire to the surrounding houses.

After that episode, the Christians issued an edict that no Christian girl could be seen with a Muslim boy. “We had a problem of intermarriage,” Pastor Sunday Wuyep, a church leader in Yelwa, told me on the first of two visits I made in 2006 and 2007. “Just because our ladies are stupid and attracted to money,” he sighed. Economics lay at the heart of the enmity between the two groups: as merchants and herders, the Muslim Jarawa were much wealthier than the Christian Tarok and Goemai. But Pastor Sunday, like many others of his faith, felt that Muslims were trying to wipe out Christians by converting them through marriage. “It’s scriptural, this fight,” he said. So he and the other elders decided to punish the women. “If a woman gets caught with a Muslim man,” Sunday said, “she must be forcibly brought back.” The decree turned out to be a call to vigilante violence as patrols of young men, both Christian and Muslim, took to the streets. What eventually transpired, in the name of religion, was a kind of Clockwork Orange.

Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country, with 140 million people (one-seventh of all Africans), and it’s one of the few nations divided almost evenly between Christians and Muslims. Blessed with the world’s 10th-largest oil reserves, it is also one of the continent’s richest and most influential powers—as well as one of its most corrupt democracies. Last year’s presidential election in particular—in which President Olusegun Obasanjo, an evangelical Christian, handed power to a northern Muslim, President Umaru Yar’Adua—was a farce. Ballot boxes were stuffed by thugs or carted off empty by armed heavies in the pay of political candidates. Across the country, political power is a passport to wealth: according to Human Rights Watch, anywhere from $4 billion to $8 billion in government money has been embezzled annually for the last eight years. The state has all but abdicated its responsibility for the welfare of its people, roughly half of whom live on less than $1 a day.

In this vacuum, religion has become a powerful source of identity. Northern Nigeria has one of Africa’s oldest and most devout Islamic communities, which was galvanized, like many others, in the 1980s by the global Islamic reawakening that followed the Iranian revolution. For Christians, too, in Nigeria, there’s been a revolution: high birthrates and aggressive evangelization over the past century have increased the number of believers from 176,000, or 1.1 percent of the early-20th-century population, to more than 51 million, or more than a third now. Thanks to this explosive growth, the demographic and geographic center of global Christianity will have moved, by 2050, to northern Nigeria, within the Muslim world.

No one knows what this shift will yield, in part because neither faith is a monolith. Indeed, the most overlooked aspect of this global religious encounter may be that the competition within the faiths—between Pentecostals and orthodox Christians, or between Islamic groups that want to engage with or reject the modern world—is just as important as the competition between the faiths. But it’s also true that the fastest-growing forms of faith on both sides tend to be the most effervescent and absolute. They promote a system of living in this world that promises heaven in the next, they see salvation in stark binary terms, and they believe they have a global mandate to spread their exclusive brand of faith.

While religion became a source of friction in Nigeria during the Biafran civil war in the late 1960s, the trouble between Christians and Muslims intensified in the 1980s, when the first oil boom fizzled and the ensuing economic downturn led to violence. Since then, thousands have been killed in riots between the two groups sparked by various events: aggressive campaigns by foreign evangelists; the implementation in 1999 and 2000 of sharia, or Islamic law, in 12 of Nigeria’s 36 states; the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan in 2001; and the 2002 Miss World pageant, when a local Christian reporter, Isioma Daniel, outraged Muslims by writing in one of Nigeria’s national papers, This Day, that the Prophet Muhammad would have chosen a wife from among the contestants. Most recently, in 2006, riots triggered by Danish cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad left more people dead in Nigeria than anywhere else in the world.

“These conflicts are a result of secular processes,” said Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, one of Nigeria’s leading intellectuals and a top executive of one of the country’s oldest banks, FirstBank. “It’s about bad government, economic inequality, and poverty—a struggle for resources.” When a government fails its people, they turn elsewhere to safeguard themselves and their futures, and in Nigeria at the beginning of the 21st century, they have turned first to religion. Here, then, is the truth behind what Samuel Huntington famously calls religion’s “bloody” geographic borders: outbreaks of violence result not simply from a clash between two powerful religious monoliths, but from tensions at the most vulnerable edges where they meet—zones of desperation and official neglect where faith becomes a rallying cry in the struggle for land, water, and work.

In Nigeria, the two faiths meet along a band of terrain roughly 200 miles wide called the Middle Belt. This swath of land, for the most part (an exception being Nigeria’s southwest), marks the fault line between Christianity and Islam not only in Nigeria, but across the entire continent. A satellite image from Google Earth shows the Middle Belt as a gray-green strip between the equator and the 10th parallel, dividing the fawn-colored dry land from the vibrant sub-Saharan jungle canopy. It also separates most of the continent’s 367 million Muslims to the north from 417 million Christians to the south. Plagued by bad government, a shortage of water and arable land, and rising birthrates, the Middle Belt is also the victim of environmental change: growing aridity in the north (the desert creeps forward at slightly less than half a mile a year) and flooding in the south. Shifting weather patterns have made planting and grazing seasons unpredictable and allowed insect-borne diseases, such as malaria, to run rampant.

Islam all but stopped its southward spread here in the late 1800s, because the traders, missionaries, and Sufi jihadists who had carried Islam south couldn’t handle the jungle terrain or the tsetse flies that plagued their horses and camels with sleeping sickness. Abdullahi’s people, the Jarawa, claim that their rights to the land go back to the days of Usman Dan Fodio, a Sufi teacher and ethnic Fulani herder who launched a 19th-century jihad to purify the faith, promote the education of women, and outlaw the enslavement of his fellow Muslims. Some of his jihadists, called his flag bearers, rode south over vast reaches of dry land until they reached the southern edge of the Sahel, roughly where the town of Yelwa is today.

The high, dry ridges and rocky escarpments of the Middle Belt also provided an ideal defense against Muslim slave raiders for non-Muslim hill people like the Goemai. When Christian missionaries arrived 100 years ago, many targeted these “pagan” hill people. For some, the mission was to create a buffer against the southern “spread of Mohammedanism,” as Karl Kumm, one of the more uncompromising missionaries, put it. But many of his coreligionists had little interest in combating Islam. Instead, armed with the two B’s of Bible and bicycle, as well as with the imperative of self-reliance, they dispensed practical advice on health, agriculture, and eventually education, providing a form of “emancipation” for the historically disenfranchised hill people, who also gained a powerful collective identity in Christianity.

The British colonial administration was ambivalent about missionaries, fearing that their efforts to convert Muslims would destabilize Britain’s plans for empire-building—as they had elsewhere in Africa. When the British overthrew the caliphate, then unified North and South Nigeria in 1914, the new colonial administration forbade missionaries to enter Muslim lands. Under the British policy of Indirect Rule, which was modeled on the Raj in India, Dan Fodio’s emirs were largely left in place. Many came to be seen as colonial agents, losing their religious legitimacy even as they amassed power and wealth. This colonial policy of favoring Muslims over minority Christians left a legacy of mistrust between the two groups. “Every crisis is automatically interpreted as a religious crisis,” said Archbishop Josiah Idowu-Fearon, the Anglican bishop of Kaduna. “But we all know that, scratch the surface and it’s got nothing to do with religion. It’s power.”

One Tuesday at 7 a.m. in Yelwa, about 70 people were praying their morning devotions at the Church of Christ in Nigeria (founded by none other than the fiery Kumm himself). It was in February 2004, about a year after the elders had issued their edict that no Christian woman was to be seen with a Muslim man. As the worshippers finished their prayers, they heard gunshots and a call from the loudspeakers of the mosque next door: “Allahu Akhbar, let us go for jihad.” “We were terrified,” recalled Pastor Sunday, who had been standing outside the gate as the churchyard swarmed with strangers. He stayed near the church gate, but many other people fled toward the road behind the church. There, men dressed in military fatigues reassured them that they were safe and herded them back to the church. Then the men opened fire.

Pastor Sunday fled; that’s why he survived. The attackers—who were not, in fact, Nigerian soldiers—set the church on fire and killed everyone who tried to escape. They chased the head of the church, Pastor Sampson Bukar, to his house next door and ran him through with cutlasses. They set fire to the nursery school and the pastor’s house. During my first visit to Yelwa in the summer of 2006, his burned Peugeot was still outside. The church had been rebuilt and painted salmon pink. Boys were playing soccer, each wearing only one shoe so that everyone could kick the ball. “Seven in my family were killed,” said Sunday as we sat in the churchyard. “We call them martyrs.” He pointed to a mound of earth not far from where we were sitting. On top was a small wooden cross: it marked the mass grave for the 78 people killed that day.

“This is about religious intolerance,” he went on. “Our God is different than the Muslim God … If he were the same God, we wouldn’t fight.” For Pastor Sunday, the clash was millenarian and grounded in the literal words of Christian scripture. “The Bible says in Matthew 24, the time will come when they will pursue us in our churches,” he said. Matthew 24 foretells the Tribulation: the war that will precede Armageddon and the final coming of Jesus.

A few hundred yards down the road from the church, there’s a cornfield. In it, a row of mounds: more mass graves. White signs tally the dead below in green paint: 110, 50, 65, 100, 55, 25, 60, 20, 40, 105. Two months after the church was razed, Christian men and boys surrounded Yelwa. Many were bare-chested; others wore shirts on which they’d reportedly pinned white name tags identifying them as members of the Christian Association of Nigeria, an umbrella organization founded in the 1970s to give Christians a collective and unified voice as strong as that of Muslims. Each tag had a number instead of a name: a code, it seemed, for identification. They attacked the town. According to Human Rights Watch, 660 Muslims were massacred over the course of the next two days, including the patients in the Al-Amin clinic. Twelve mosques and 300 houses went up in flames. Young girls were marched to a nearby Christian town and forced to eat pork and drink alcohol. Many were raped, and 50 were killed.

Yelwa was still a ghost town of sorts in August 2006. In block after burned-out block, people camped in what used to be their homes. The road was lined with more than a dozen ruined mosques and churches, but the rubble was hidden in hip-high elephant grass; canary-yellow morning glories climbed the old foundations. When I arrived at the home of Abdullahi, the Muslim human-rights lawyer, his street was mostly deserted. He stooped on his way out of a low-ceilinged hut. Behind him, I could see the sour faces of a man and woman sitting on the floor by his desk. “Marital dispute,” he explained.

It was the rainy season, so I waited out the noon deluge in another small hut on his compound. Finally, Abdullahi ducked inside, a worn accordion file under his arm. His wife followed, carrying a pot of hot spaghetti. In the beginning, he explained, the conflict in Nigeria had nothing whatsoever to do with religion. “Let me give myself as a case study,” Abdullahi said. He went to Christian mission schools and federal college, and never, as a Muslim, had any problem. “Throughout this period, I’d never seen religious segregation, because at that time the societal value system was intact. We were taught to respect each other’s beliefs and customs.” But as the population grew and resources shrank, people began to fight over who had the right to the land and its resources—who belonged as an indigene, and who didn’t.

Abdullahi has attempted to bring several cases of ethnic abuse to the government’s attention, but as with the church massacre, the government has done little to investigate or to try those involved. He handed me a folder with depositions from one such case. As I read them, Abdullahi returned with two young women, Hamamatu Danladi and Yasira Ibrahim, who had survived the incident detailed in the files. Danladi met my eye as she stood in the doorway; Ibrahim, with long upturned lashes and a moon face, didn’t. Abdullahi invited the women in, lowered his head, and left.

During the Christian attack, the two young women took shelter in an elder’s guarded home. On the second day, the Christian militia arrived at the house. They were covered in red and blue paint and were wearing those numbered white name tags. The Christians first killed the guards, then chose among the women. With others, the two young women were marched toward the Christian village. “They were killing children on the road,” Danladi said. Outside the elementary school, her abductor grabbed hold of two Muslim boys she knew, 9 and 10 years old. Along with other men, he took a machete to them until they were in pieces, then wrapped the pieces in a rubber tire and set it on fire.

When Danladi and Ibrahim reached their captors’ village, they were forced to drink alcohol and to eat pork and dog meat. Although she was obviously pregnant, Danladi’s abductor repeatedly raped her during the next four days. After a month, the police fetched Danladi and Ibrahim from the Christian village and took them to the camp where most of the town’s Muslim residents had fled. There, the two young women were reunited with their husbands. They never discussed what happened in the bush.

“The Christians don’t want us here because they don’t like our religion,” Danladi said. “Do you really think they took you because of your religion?” I asked. The women looked at each other. “In Islamic history, there are times when believers and nonbelievers have fought,” Danladi said. “We think what happened here is part of the clash that will come. After the clash, people will see poverty and suffering and that’s what’s happening now. According to our ulamas [teachers], there is no way that the whole world will not be Muslim.”

Later, I looked up Matthew 24, the verses that Pastor Sunday had cited. In many versions of the Bible, Jesus’ words are inked in red to show that these are the exact and inerrant words of the Lord. Down the rice-paper page, one red verse (Matthew 24:19) caught my eye: “But woe to those who are pregnant and to those who are nursing babies in those days!” I thought of Hamamatu Danladi. After her rape, she told me, she didn’t give birth for four more months, which meant she carried that child for more than a year. Maybe I didn’t understand her. When I returned to visit her a year later, I asked again if I’d misunderstood. No, she said, she’d carried the baby for more than a year. Maybe, she thought, he simply refused to come into this world during the conflagration.

At the time of the massacre, Archbishop Peter Akinola was the president of the Christian Association of Nigeria, whose membership was implicated in the killings. He has since lost his bid for another term but, as primate of the Anglican Church of Nigeria, he is still the leader of 18 million Anglicans. He is a colleague of my father, who was the presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church in America from 1997 to 2006. But the American Episcopals’ election of an openly homosexual bishop in 2003, which Archbishop Akinola denounced as “satanic,” created distance between them. When I arrived in 2006 in the capital of Abuja to see the archbishop, his office door was locked. Its complicated buzzing-in system was malfunctioning, and he was trapped inside. Finally, after several minutes, the angry buzzes stopped and I could hear a man behind the door rise and come across the floor. The archbishop, in a pale-blue pantsuit and a darker-blue crushed-velvet hat, opened the door.

“My views on Islam are well known: I have nothing more to say,” he said, as we sat down. Archbishop Akinola has repeatedly spoken critically about Islam and liberal Western Protestants, and he was understandably wary of my motives for asking his thoughts. For Akinola, the relationship between liberal Protestants and Islam is straightforward: if Western Christians abandon conservative morals, then the global Church will be weakened in its struggle against Islam. “When you have this attack on Christians in Yelwa, and there are no arrests, Christians become dhimmi, the vocabulary within Islam that allows Christians and Jews to be seen as second-class citizens. You are subject to the Muslims. You have no rights.”

When asked if those wearing name tags that read “Christian Association of Nigeria” had been sent to the Muslim part of Yelwa, the archbishop grinned. “No comment,” he said. “No Christian would pray for violence, but it would be utterly naive to sweep this issue of Islam under the carpet.” He went on, “I’m not out to combat anybody. I’m only doing what the Holy Spirit tells me to do. I’m living my faith, practicing and preaching that Jesus Christ is the one and only way to God, and they respect me for it. They know where we stand. I’ve said before: let no Muslim think they have the monopoly on violence.”

Archbishop Akinola, 63, is a Yoruba, a member of an ethnic group from southwestern Nigeria, where Christians and Muslims coexist peacefully. But the archbishop’s understanding of Islam was forged by his experience in the north, where he watched the persecution of a Christian minority. He was more interested during our interview, though, in talking about the West than about Nigeria.

“People are thinking that Islam is an issue in Africa and Asia, but you in the West are sitting on explosives.” What people in the West don’t understand, he said, “is that what Islam failed to accomplish by the sword in the eighth century, it’s trying to do by immigration so that Muslims become citizens and demand their rights. A Muslim man has four wives; the wives have four or five children each. This is how they turned Christians into a minority in North Africa.”

He went on, “The West has thrown God out, and Islam is filling that vacuum for you, and now your Christian heritage is being destroyed … You people are so afraid of being accused of being Islam-phobic. Consequently everyone recedes and says nothing … Over the years, Christians have been so naive—avoiding politics, economics, and the military because they’re dirty business. The missionaries taught that. Dress in tatters. Wear your bedroom slippers. Be poor. But Christians are beginning to wake up to the fact that money isn’t evil, the love of money is, and it isn’t wrong to have some of it. Neither is politics.”

Democracy, Nigerians told me repeatedly, is a numbers game. That’s why whoever has more believers is on top. In that competition, Christianity has a recruiting tool beyond the frontline gospel preached by those such as Archbishop Akinola: Pentecostalism, one of the world’s most diverse and fastest-growing religious movements. In Nigeria, the oil boom of the 1970s brought a massive movement of people into cities looking for work. That boom’s collapse spurred the growth of the Pentecostal Gospel of Prosperity, with its emphasis on good health and getting rich; and of the African Initiated Churches, or AICs, which began about 100 years ago, when several charismatic African prophets successfully converted millions to Christianity. Today, AIC members account for one-quarter of Africa’s 417 million Christians.

One bustling Pentecostal hub, Canaanland, the 565-acre headquarters of the Living Faith Church, has three banks, a bakery, and its own university, Covenant, which is the sister school of Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Canaanland is about an hour and a half north of Lagos, which has an estimated population of 12 million and is projected to become the world’s 12th-largest city by 2020. With 300,000 people worshipping at a single service at the Canaanland headquarters alone and 300 branches across the country, Living Faith is one of Nigeria’s megachurches, and the dapper Bishop David Oyedepo is its prophet. The bishop, whose bald pate glistens above deep-set eyes and dazzling teeth, never wanted to be pastor: he had no interest in being poor, he told me. “When God made me a pastor, I wept. I hated poverty in the Church—how can the children of God live as rats?”

Bishop Oyedepo built Canaanland to preach the Gospel of Prosperity. As he said, “If God is truly a father, there is no father that wants his children to be beggars. He wants them to prosper.” In the parking lot at Canaanland, beyond the massive complex of unusually clean toilets, flapping banners promise: Whatsoever you ask in my name, he shall give you, and By his stripes he gives us blessings.

The Pentecostal movement is so vast and varied, it’s a mistake to generalize about its unifying principles. But Pentecostals do tend to share an experience of the Holy Spirit, or the numinous, that offers the gift of salvation and success in everyday life—particularly in the realms of personal health and finance. Archbishop Akinola, whose own Anglican Church is more threatened in some ways by the rise of Pentecostalism than by the rise of Islam, finds these teachings suspect: “When you preach prosperity and not suffering, any Christianity devoid of the cross is a pseudo-religion.”

But Bishop Oyedepo’s followers say that those who criticize don’t understand what’s happening in Africa. “There’s a kind of revolution going on in Africa,” one of the bishop’s employees, Professor Prince Famous Izedonmi, said. “America tolerates God. Africa celebrates God. We’re called ‘the continent of darkness,’ but that’s when you appreciate the light. Jesus is the light.” The professor, a Muslim prince who converted to Christianity as a child to cure himself of migraine headaches, was the head of Covenant University’s accounting department and director of its Centre for Entrepreneurial Development Studies.

“God isn’t against wealth,” Professor Famous said. “Revelations talks about streets paved with gold.” He added, “Look at how Jesus dressed.” When I appeared baffled, he patiently explained that since the soldiers cast lots for Christ’s clothes, they were clearly expensive. In Canaanland, clothes matter: the pastors wear flashy ones and they drive fast cars as a sign of God’s favor. They draw their salaries from sizable weekly contributions. On Sundays at some Nigerian Pentecostal churches, armored bank trucks reportedly idle in church parking lots, while during the service, believers hand over cash, cell phones, cars—all with the belief that if they give to God, God will make them rich. It’s said that if the Christian Prosperity churches disappeared, the banks of Nigeria would collapse.

But to see the Prosperity movement as simply a get-rich-quick scheme is to miss its importance. In many ways, Pentecostalism has updated Max Weber’s Protestant work ethic for the 21st century. Pentecostals do not drink, gamble, or engage in extramarital sex; so all of that formerly illicit energy can go into either business or education. Covenant has been voted the best private university in Nigeria by Nigeria’s National Universities Commission. Education is an essential element of the Prosperity message; so is hard work. “Abraham was a workaholic,” Professor Famous said. “He worked 16 or 17 hours a day.”

During my first visit to Covenant, school wasn’t in session, so I poked around the empty labs until I ran into a lone student, Mchenson Ugwu, 22, studying mechanical engineering in hopes of getting a job in the oil industry. Ugwu was born again in 2004. “Once in a while I backslide and have to rededicate my life to Christ,” he said. “That’s how it works: backslide, rededicate.” For Ugwu, salvation had very little to do with the next world; it was all about this one. “Because he owns everything here on Earth, if you make God your father, beginning and end, he’ll keep you up. Our bishop is the perfect example. He tells us he hasn’t been poor in 25 years, and God takes him from one level to the next.”

Later, the bishop led me across his red shag carpet to a white fountain tinkling in the corner of his office. “The problem with the African man is that he sees himself as poor, and others see him as poor,” the bishop said. He walked over to his desk and handed me a stack of his books—he’s written 60—including one of the best sellers, Understanding Financial Prosperity. The cover design features Nigerian banknotes. The back cover reads: “I am not a preacher of prosperity, I am a prophet. God spoke specifically to me while I was away in America for a meeting, ‘Get down home and make My people rich!’”

The Christian Gospel of Prosperity is so powerful that it has spawned a unique Nigerian phenomenon: an Islamic organization called Nasrul-Lahi-il-Fathi (NASFAT). The name is drawn from a verse in the eighth chapter of the Koran: “There is no help except from Allah.” This is the same chapter, “The Spoils of War,” or Al-Anfal, that Saddam Hussein cited to justify his genocide against the Kurds. But NASFAT has no interest in violence. Instead, the organization is based on economic empowerment and prosperity with an Islamic spin. Started with about a dozen members in the 1990s, NASFAT now has 1.2 million members in Nigeria and branches in 25 other countries. The organization has an entrepreneurship program, a clinic, a prison-outreach program, a task force to address HIV/AIDS, a travel agency, and a soft-drink company called Nasmalt, whose profits go to the poor. It even offers matchmaking. Although many conservatives believe that this engagement with the secular world is haram, forbidden, and distinctly un-Islamic, NASFAT argues that it is the only way to survive in the marketplace.

“We are competing for faithfuls,” NASFAT’s executive secretary, Zikrullah Kunle Hassan, said one blistering Sunday last August in Lagos. “Many people now want God. This is happening especially among the youth, that they feel they need to be committed to faith.” Gesturing to the streets choked with more than 100,000 men and women clad in shining white as they came from a prayer service at the Lagos Secretariat Mosque, he explained that NASFAT meets on Sundays so that Muslims have something to do while Christians attend church. “The space on Sunday is usually not dominated by Islam, but other faiths and other values. But when our people come here, they come and drink from the fountain of Islam.”

The prayer ground looked like a fair. Hawkers sold lemons from a wheelbarrow. Small booths offered pretty, scalloped hijabs, embroidered with “NASFAT” in blue. Men sat on prayer mats eating rice, while women attended a lecture on ways to make money that are in keeping with Islam.

NASFAT’s primary mission is to reclaim those values the world sees as Western, but which its members perceive as integral to the success of the global Islamic community, or ummah. Foremost is education. “We know that the West is ahead today because of education,” Hassan said. NASFAT has its own nursery, primary, and secondary schools, as well as the brand-new Fountain University. While many orthodox believers say that this new movement is bi’dah, innovation, and therefore dangerously un-Islamic, NASFAT’s adherents disagree, arguing that they are part of a charismatic Muslim movement that addresses social welfare—and that is on its way to sweeping the world. (They’re also mostly Muslims from Nigeria’s southwest, which means they grew up around Christianity and are more comfortable with its ways.) If every answer to life can be found in the Koran, Hassan said, then questions of how to survive and prosper must be addressed there. When conservative northern clerics kick up a fuss about NASFAT’s growing presence in the communities, NASFAT reaches out to them with gestures like involving community youth in business programs.

“To be honest, for us there’s a competition of civilizations, there’s a competition of values, and to me, the roots of the conflict are that we believe all civilizations have collapsed in the face of Western civilization,” he went on. “Communism collapsed. All other values collapsed. Islam remained resistant to Western civilization.” In order to survive, Islam has to address the contemporary needs of its people and compete with the Christian promise of prosperity. As one young member, who joined the organization to get a job through its business network, told me, “There’s nothing you want to achieve that NASFAT can’t help you get, here in this country.” He added, “Success, triumph, and glory are from the Creator.”

"Prosperity Gospel is more a symptom than the disease,” Father Matthew Hassan Kukah, the Roman Catholic author of Religion, Politics and Power in Northern Nigeria, told me in his office above a Catholic church in the city of Kaduna, at the northern edge of the Middle Belt. To his mind, Nigerians’ resort to religion to achieve prosperity was a natural response to their corrupt political landscape and the absence of any civil government. “You can buy a car and insure it,” he continued. “You don’t need a priest to pray over the car, to bless your house to keep robbers away … Here, there’s no guarantee. God is being called upon to police a lot of areas of our lives.” This need for God’s protection isn’t only individual, but collective and political, given the collapse of the state.

Many Muslims share that point of view. Take, for example, the ongoing effort to implement sharia, or Islamic law, in northern Nigeria, which came to fruition in 1999. On a practical level, sharia, with its promise of moral justice at the local level, seems to offer an end to the corruption that bedevils the people. And given that many Nigerians associate that corruption with the failure of Western-style democracy in Africa, “to reinstate the sharia … is not only good religion, it is supremely sound politics,” argues Murray Last, an emeritus professor at University College London.

Yet despite a huge outcry from Christians and the West, the implementation of sharia, which is currently on the books in 12 of Nigeria’s 36 states, has had very little practical impact. The harsh criminal punishments spelled out in the hudud have proven, for the most part, impossible to implement. And northern Nigerians have now seen that sharia has not stanched the corruption they face every day. In fact, many of the politicians who backed sharia have been linked to massive corruption; these include the biggest advocate, the former governor of Zamfara state, who is even rumored to have paid a man to let the state amputate his hand for stealing livestock.

So if religion has proven not to safeguard the car, not to cure malaria, not even to stop politicians from stuffing ballot boxes, is it worth fighting and dying for? Popular disillusionment is one reason why Father Kukah believes that Nigeria’s religious mayhem is an isolated stage in its development of plural stability. Paradoxically, this progression is clearest in Kaduna, formerly one of the most intense flash points, where Kukah lives. Over the past 20 years, many of the city’s churches and mosques have been burned down, and thousands of residents have been killed in battles fueled by religion. Kaduna, whose name means “crocodile,” is a microcosm of Nigeria: its population of 1.5 million people is divided in half between Muslims and Christians. The split isn’t just demographic; it’s geographic. The city’s Muslim neighborhoods—nicknamed Baghdad and Afghanistan—are on the north side of town. The Christian ones—called Television, Haifa, and Jerusalem—are on the south side. The Kaduna River separates them.

Pastor James Movel Wuye was born in Kaduna into an ethnic minority called Gbagyi. Historically, his people were aboriginal warriors who fought off Hausa Muslim slave raiders before the arrival of the British, who actually made things worse. “They were merciless, the Muslims who were ruling over us,” he said. His people still call the Hausa Muslims ajei, which means “those who trouble us.” Pastor James’s father was a soldier, and when James and the other barracks boys played war, their imagined enemies were their Hausa oppressors. As a teenager, James rebelled: he drank and smoked, and he wooed a long list of girlfriends. He also joined the Christian Association of Nigeria and, at 27, became general secretary of the Youth Wing. In 1987, the Middle Belt exploded. When fighting between Christians and Muslims reached Kaduna, Pastor James became the head of a Christian militia. “We took an oath of secrecy,” he said. “We carried pictures of those [of us] who’d been killed. We were martyrs: we felt that we were dying in defense of the Church.” The war, like the faith itself, became a struggle for liberation.

James incited violence by relying on the literal, inspired word of scripture. “I used to say, ‘We’ve been beaten on both cheeks, there’s no other cheek to turn,’” he said. “I used Luke 22:36: as Jesus said to the disciples the night before his crucifixion, ‘And if you don’t have a sword, sell your cloak and buy one.’” When the pastor was 32, a fight broke out between Christians and Muslims over control of a market. “That day, we were outnumbered,” he said. “Twenty of my friends were killed. I passed out, so I don’t know exactly what happened.” When he woke up, his right arm was gone, sliced off with a machete.

Imam Muhammad Nurayn Ashafa is also a former militia leader, from the other side of the river, where he still lives. “We were fighting on either side of town, James and I,” he told me when I first visited his home in August 2006. Ashafa’s life is equally steeped in the history of his people. He comes from a long line of Muslim scholars who were powerful under the caliphate of Usman Dan Fodio, and his story, too, is a tale of oppression and reaction to oppression. “My family had, all its life, struggled against colonialists and missionaries because they watched the colonialists bring Christianity into the hinterlands. I grew up hearing stories of how our land was stolen and our people were crushed.” When Ashafa was a boy, his father refused to let him go to school, because missionaries ran the school. “Missionaries are evil,” he told his son. But Ashafa’s uncle talked his father into it, saying, “Let the boy go to school. Don’t you trust your God?”

At mission school, Ashafa won the prize for best Bible student; he had a gift for memorization. After school, Ashafa would use a slingshot to fling stones at women who were showing their bare arms or backs in the streets. When the religious crisis hit Kaduna in 1987, Ashafa, like James, became a militia leader. The two were enemies. “We planted the seed of genocide, and we used the scripture to do that,” Ashafa said. “In Islam, you must fight in defense of any women, children, or old people—Muslim or not—so as a leader, you create a scenario where this is the only interpretation,” he explained. But Ashafa’s mentor, a Sufi hermit, tried to warn the young man away from violence. “You will not cross the ocean with hate in your heart,” he told Ashafa.

In 1992, Christian militiamen stabbed the hermit to death and threw his body down a well. Ashafa’s only mission became revenge: he was going to kill James. Then, one Friday during a sermon, Ashafa’s imam told the story of when the Prophet Muhammad had gone to preach at Ta’if, a town about 70 miles southeast of Mecca. Bleeding after being stoned and cast out of town, Muhammad was visited by an angel who asked if he’d like those who mistreated him to be destroyed. Muhammad said no. “The imam was talking directly to me,” Ashafa said. During the sermon, he began to cry. Next time he met James, he’d forgiven him entirely. To prove it, he went to visit James’s sick mother in the hospital.

Slowly, the pastor and the imam began to work together, but James was leery. “Ashafa carries the psychological mark. I carry the physical and psychological mark,” he said. “He talks so much. I’m a little miserly with words. So when he uses his energy like that, he sleeps very deeply. There were instances where we shared a room. He’s a very heavy sleeper. You can actually take the pillow off his head and he will just struggle and go back to sleep. More than once, several times, I was tempted to use the pillow to suffocate him. But this restraining force of the deepness of my faith comes ringing through my ears.”

At a Christian conference in Nigeria sponsored by Pat Robertson—one of the most anti-Muslim preachers in the world—a fellow pastor pulled James aside and said, in almost the same words as the Sufi hermit, “You can’t preach Jesus with hate in your heart.” James said, “That was my real turning point. I came back totally deprogrammed. I know Pat Robertson might have had another agenda, but I was truly changed.”

For more than a decade now, James and Ashafa have traveled to Nigerian cities and to other countries where Christians and Muslims are fighting. They tell their stories of how they manipulated religious texts to get young people into the streets to shed blood. Both still adhere strictly to the scripture; they just read it more deeply and emphasize different verses.

Nonbelievers may wonder how these “deprogramming” efforts can actually work. But religion is the X factor in conflicts like Nigeria’s, which can’t be reduced just to economics. As Barbara Cooper, the author of Evangelical Christians in the Muslim Sahel, puts it, “Faith matters.”

Pastor James sent me on a tour of Kaduna with one of his employees, Haruna Yakubu, a former Islamic militant who now works as a youth coordinator for the Interfaith Mediation Centre, which the pair of religious allies founded. Yakubu took me to see the poured-cement skeleton of the fire-ravaged Alafia Oluwa Baptist Church. “The Baptists want to sell it,” Yakubu said, as we climbed out of the pastor’s aging Mercedes. The cross and spire had been sheared off, but the walls and heavy cement Romanesque arches were still standing. They now enclosed a large grassy field; a cow was tethered to a tree. I walked toward the narthex, but Yakubu stopped me. It stank of human excrement. “The locals have turned it into a toilet,” he said, uncomfortably. On the wall, through a hole blasted into the cement, someone had painted a picture of a naked woman, a penis with “Pastor S—” written on it pointed between her spread legs. “We’re trying to convince the Baptists to come back, but they don’t want to.” I could see why. I couldn’t imagine a more desecrated place. In 2007, the Christians sold it after all. When Yakubu and I drove by a year after our first visit, the word masalaci, which means “mosque,” had been spray-painted across it in red.

We drove in silence. Yakubu looked out of the car’s smeared window at the colonial-era ash trees lining the broad road toward the polo ground. “Our religious leaders are some of our most dangerous people,” he said. “They preach that they want us to go back to Medina, but we can’t go back to Medina.” Medina, the city in which Muhammad led an army and a state, has different connotations than Mecca, the city of his youth. In the Koran, the verses from Medina speak frequently of war and violence, unlike the ones from Mecca. “Even the Prophet lived with Christians; why can’t we? If we call ourselves true Muslims, why can’t we do that?” said Yakubu.

Along the road, red-eyed boys sold jerricans of petrol. Nigeria is the United States’ fifth-largest supplier of oil, but because of corruption and mismanagement, it imports much of its gasoline. During price hikes and shortages, these young hawkers appear by the roadside. Such boys are the first to join the fighting; their gas cans become weapons. Usually someone’s paying them. In the north, there are millions of these jobless and school-less young men. For the price of a meal, they form a ready army.

One Friday before afternoon prayer, I visited Imam Ashafa at home. He’d already solved three neighborhood disputes that morning. Two smiling old men wearing dark glasses sat on his green sectional couch. Both were blind, and the imam had started a foundation to help them. His two young wives, Fatima and Aisha, both disarmingly warm and very attractive, served tea on top of a tin canister. “I like pretty women,” the imam told me later. The room was stuffy: the windows were shut and the green-and-white striped curtains drawn in purdah. On one closed door, a bumper sticker read Combat AIDS with Shari’a. The method was clear: abstinence. The imam and the pastor share the same conservative moral values, which has also helped them to find common ground.

Frequently, the problems each confronted weren’t divisions between Christians and Muslims, but arguments within his own side. One of Ashafa’s greatest challenges is to manage Kaduna’s growing list of Muslim groups at odds with each other. The self-proclaimed Shia of northern Nigeria are closely tied to Iran. They’re engaged in a cold war—which sometimes heats up—with a radical group of Sunnis. Some Sunni hardliners, in turn, rail against what they see as the “corrupt” Islam practiced by Nigeria’s Sufi majority. As among the Christians, the divisions between the Muslims continue to deepen—a splintering that undermines any facile notions of a global clash of two monoliths. Still, the imam is frequently accused of being a sellout because he associates with Christians. He identifies himself very much as a fundamentalist and sees himself as one who emulates Muhammad. Although he and Pastor James don’t discuss it, he also proselytizes among Christians. “I want James to die as a Muslim, and he wants me to die as a Christian. My Islam is proselytizing. It’s about bringing the whole world to Islam,” he told me that day.

Such missionary zeal drives both men, infusing their struggle to rise above their history of conflict with the same undercurrent of competitive tension that runs across the Middle Belt and the continent. As Pastor James told me at his office, Peace Hall, in Kaduna, he still believes strongly in absolute and exclusive salvation mandated by the gospel: “Jesus said, ‘I am the way and the truth and the life.’” He still challenges Christians to rely on the strict and literal word, and he’s still uncompromising on fundamental issues of Christianity. “We see same-sex marriages in the United States as signs of end times: it’s Sodom and Gomorrah,” he told me. “But I also want to say you can believe what you want to believe. We have to find a space for coexistence.”

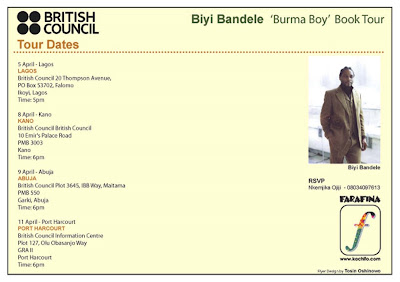

Really interesting looking show at the Studio Museum Harlem on emerging African artists working in the diaspora - click here for more. Thanks Obinna for the link. If anyone goes to the show, I'd be grateful if you could email me a write-up - I will post to this site - or send me a link to your blog write-up.

Really interesting looking show at the Studio Museum Harlem on emerging African artists working in the diaspora - click here for more. Thanks Obinna for the link. If anyone goes to the show, I'd be grateful if you could email me a write-up - I will post to this site - or send me a link to your blog write-up.